Morning Tiebreak: Pre-Australian Open Roundup

Resurgent FAA, Putintseva's hold percentage, Vive La Monf, and more

Welcome to the first iteration of Morning Tiebreak, a roundup of 7 (ish) Things I liked (inspired by Zach Lowe’s 10 Things) in Pro Tennis over the past few weeks. Today, we’re covering the events leading up to the Australian Open. Note that these aren’t meant to cover the defining moments of the Men’s and Women’s tours, so apologies to Coco Gauff’s newfound confidence in her serve and forehand, the US winning the United Cup, Reilly Opelka beating Djokovic at Brisbane, Alexandre Müller’s Hong Kong 250 triumph, Aryna Sabalenka winning Brisbane, and many more.

Felix Auger-Aliassime, hunting the forehand

Felix Auger-Aliassime is still only 24 years old, yet the days of him being hyped as a future Grand Slam winner and the subject of a beautiful Louisa Thomas New Yorker feature seem long gone.

Rather than going gently into that good night, FAA has had a resurgent start to his 2025 season, with a win over fellow formerly hyped wunderkind Sebastian Korda in the final.

FAA’s game has not drastically changed in the last few years, and can loosely be described as “aggressive indoor hard court tennis”: big serve, big forehand, look to be on the offensive at the first available opportunity. In the Adelaide final, the forehand came alive, especially out of the Ad court:

What’s especially impressive about his Adelaide title run is that in the semi-finals and finals, he played two players in Tommy Paul and Korda who are very comfortable and capable of creating width off their backhand. Usually, players like this pose a significant problem for FAA, as he typically finds himself on the losing end of backhand to backhand exchanges. What’s more, if he tried to adjust by recovering further to his backhand side (meaning his opponent would have to hit a wider ball in order to get to FAA’s backhand), he’s vulnerable to the down the line backhand that a player like Paul or Korda are capable of hitting.

FAA’s solution? Hit fewer backhands, and recognize when you’ve hit a good one that earns you a forehand.

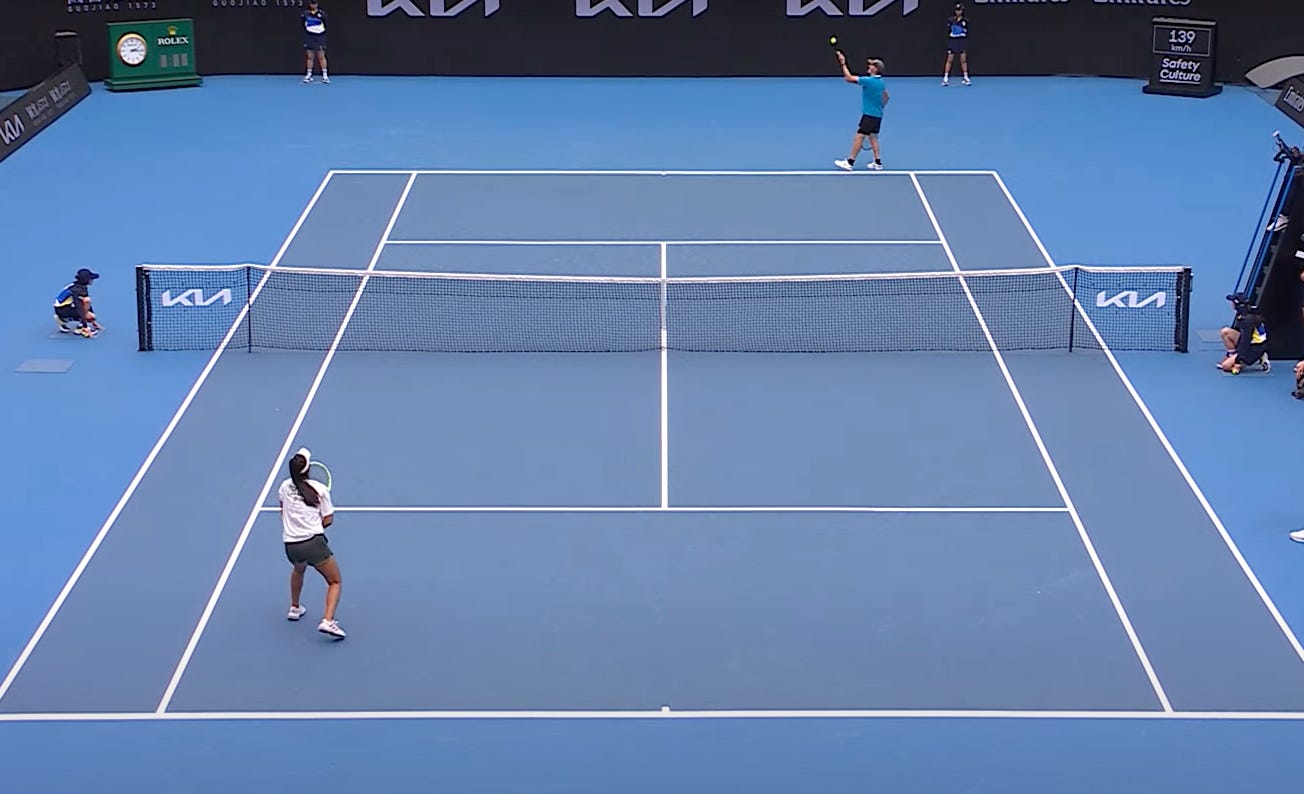

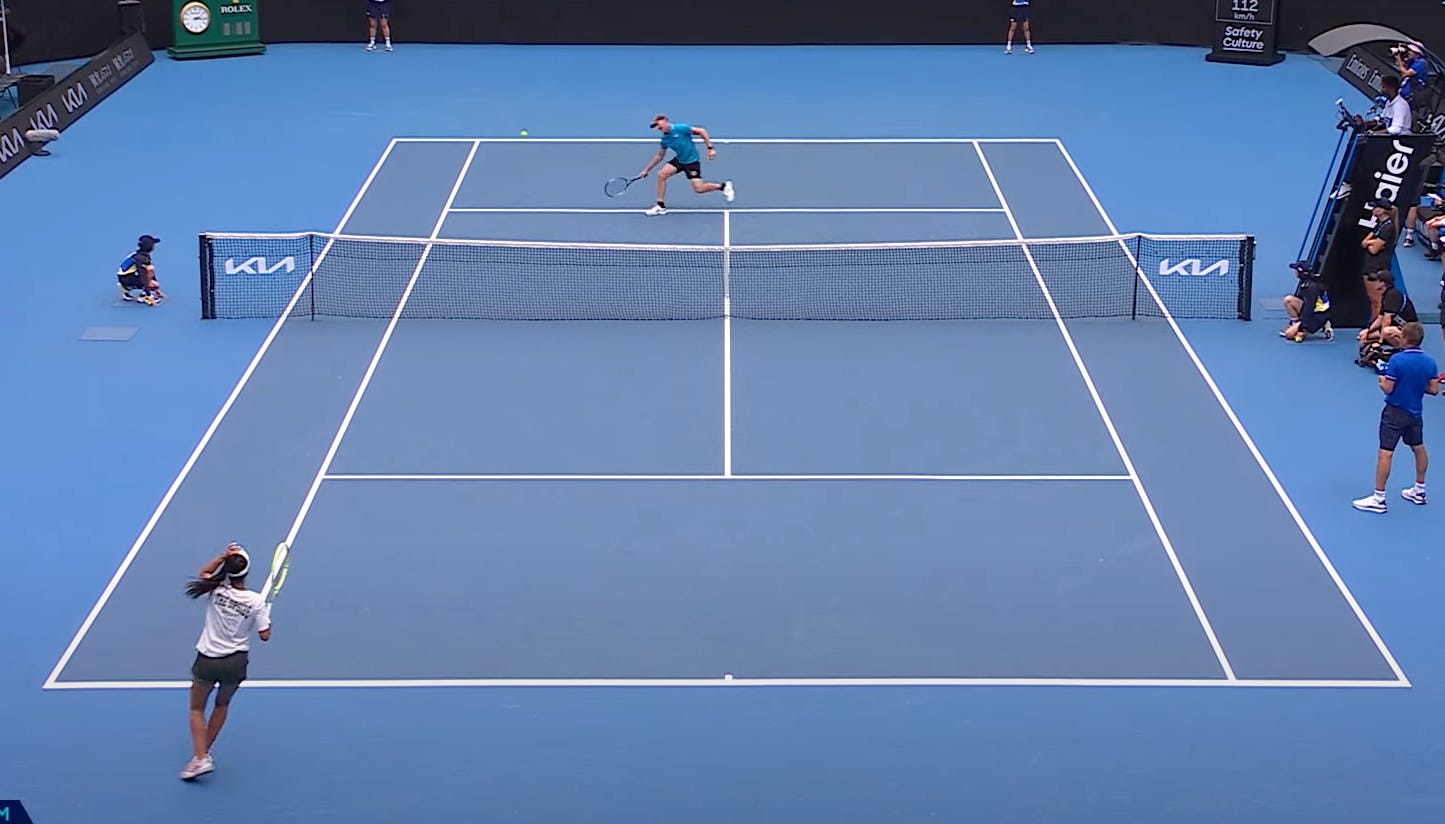

Here’s a point in his match against Tommy Paul that illustrates this:

FAA hits a first serve that Paul slices short into FAA’s backhand side. Against a player with a more reliable backhand, this is bad news, but against FAA, you can live with it. Predictably, FAA dribbles a backhand cross-court, but he shades to his left to try to maximize his chances of hitting a forehand in the next shot. He doesn’t have to worry about Paul hitting a backhand down the line yet because Paul is hitting his backhand on the run, and it’s a little too early in the point to go on offense as the returner. Paul’s backhand cross-court is decent, but FAA can run around it and hit a forehand back to Paul’s backhand.

Paul’s backhand this time is wider, and despite FAA’s pretty aggressive positioning (he has recovered to the middle between the center hash mark and the singles sideline, which leaves about 3/4 of the court open), he has to hit a backhand:

He hits a good one with depth that Paul can’t return with the same amount of depth and width. FAA recognizes this almost immediately, as evidenced by where he’s recovered to after he hits his backhand:

FAA has committed to hitting a forehand on his next shot, come hell or high water. But it’s not a complete gamble; he knows that while Paul has what looks like 90% of the court to aim at, the only way he can really hurt FAA is to drill the ball down the line (difficult given the depth of the ball that FAA hit, and the fact that Paul is hitting this ball open stance), or hit the singles sideline to force the FAA backhand. Paul’s backhand is good, but FAA is able to turn it into an aggressive inside-in forehand that gets Paul moving into the other corner.

This rally has now transitioned into the type of rally FAA likes: he’s in control and he can hit forehands. Another forehand down the line gets Paul scrambling to get the ball back with a slice, which gives FAA plenty of time to run around, load up, and hit an inside-out forehand winner to save a break point.

Here’s a similar point against Korda in the final, where Korda immediately goes after the FAA backhand off of FAA’s sliced return, FAA hits a deep backhand up the middle that Korda sends right back down the middle, allowing FAA to find the forehand and get Korda running. With the forehand, FAA is able to turn the rally from a Korda forehand to FAA backhand exchange into a deuce court forehand to forehand exchange, which results in an error from Korda.

Yulia Putintseva, Protect and (hold) Serve

Yulia Putintseva won 68.1% of her service games in 2024, which puts her in the company of Jasmine Paolini, Elise Mertens, Caroline Wozniacki, and Bianca Andreescu. That is to say, she is not a dominant server.

Across 6 matches so far in 2025 (including a Semi-Final appearance in Adelaide), Putintseva has held serve 84.6% of the time, just behind noted big servers Naomi Osaka, Elena Rybakina, and Aryna Sabalenka, and ahead of other noted big servers like Iga Świątek and Madison Keys.

Do I expect this trend to continue? Absolutely not, it will likely fall back down, and Putintseva will have to continue to rely on her return game in order to stay in the top 30. But this brief aberrational moment provides an interesting case study into how to keep service games competitive when the first serve rarely reaches 100mph.

Putintseva’s best serve is the wide serve on the deuce side. It’s the serve where her lack of speed is the least exploitable, as you want to trade off speed for more spin so it can move away from your opponent. A top player like Pegula will still be able to get to the ball, so Putintseva has to expect to hit a second ball. However, instead of retreating back to buy herself more time but risk hitting a ball running backwards, Putintseva anchors herself just behind the baseline, drives the ball back into the corner where it came from, and wrong-foots Pegula who is still moving to her recovery spot.

At 40:15 of the same service game, Putintseva goes for the wide serve again, and hits an even better spot that Pegula returns into the net.

Having an effective wide serve on the deuce court has two benefits. The first is that it forces your opponent to respect that you can hit that shot, and they have to adjust their return positioning accordingly. Look at Pegula standing with most of her body inside the doubles alley to cover the wide serve

This opens up the opportunity to sneak a serve down the middle from time to time and keep them honest. The second benefit is that even when the opponent is standing in the right place, and makes the return, they have to scramble back to position themselves for the next ball. This allows Putintseva to hit into the open court, back behind the returner, or straight at them as they’re running full speed to recover like in this next point. Putintseva keeps the pressure on Pegula after Pegula makes the return by again hitting the shot standing on the baseline, and taking time away from Pegula’s recovery:

On the Ad side, her options are a little more limited because she doesn’t have a serve that can help her create an advantage. However, she continues to show very aggressive footwork by hugging the baseline on her Serve +1, before stepping back slightly to settle into the rally. Putintseva is very capable of hitting balls on the run, and also retrieving a lot of offensive shots, and relies on her movement abilities to force an error from Pegula in this point:

Pegula eventually prevailed in this match 7:6 6:3, and managed to break serve twice, but I’m hoping Putintseva can ride the near servebot hold percentage for just a little while longer.

The Open Stance Slice

When a player is pulled so far wide on their backhand that they have to use the slice, most people go for an option where their entire back is turned to face the court:

This maximizes reach, but also means the player has to take an extra step afterwards to turn their body the right way round, and get back into play. An opponent that has aggressive attacking instincts will instantly see this as a time to rush to the net, catch the defensive player off guard, and make it hard for them the next shot.

Jasmine Paolini, Karolina Muchova, and Iga Świątek have decided that an alternative exists, where they hit a slice from an Open stance position (left leg on the outside while the body reaches over to hit the ball). Here’s Paolini’s attempt:

Paolini’s second serve gets attacked by Karolina Muchova, and Paolini has to scramble to get to the ball. But instead of turning her back to Muchova, she lunges with her left leg and reaches with her right arm to hit the slice, and is able to push back off with her left foot to recover for the next ball and eventually win the point. The open stance footwork saves her from wasting extra steps organizing her feet and turning her body to get ready for the next shot, and puts her in a better position to defend Muchova’s approach to the net.

Here’s an example from Muchova against Świątek, where she also lunges with her left leg, has a few stutter steps to recover, and eventually turns defense into a swinging forehand volley winner three shots later:

Here’s Świątek showing it off against Rybakina, with a little bit of sliding into the shot, which allows her to recover well to reach the drop volley response from Rybakina.

This is not a new shot, and the closed stance slice will still be the preferred shot because of its longer reach, but it’s fun to watch some of the most explosive and mobile movers in the WTA tour pull this one out from time to time.

Tomas Machac’s Scissor Kick Forehand

Tomas Machac might be the biggest hitter, pound-for-pound, on the ATP tour right now. Listed at 6 feet and 163 pounds, he’s not really the prototype frame you think of for a power hitter. Despite that, he hits huge off both the forehand and backhand, and pairs it with exceptional movement in and out of both corners (my rule of thumb for who’s a top mover vs a good-enough mover: the ability to slide into shots off both your dominant and non-dominant side).

But we’re not here to talk about his game style, or his will-they-won’t-they intrigue with compatriot Katerina Siniakova, or even his extremely short shorts that seem to ride up higher and higher as the match goes on. We’re here to talk about what’s quickly becoming his signature shot: the jumping scissor kick forehand.

Here’s one against Top-10 mainstay Casper Ruud, after a protracted rally in which Machac pins Ruud to his backhand side before going down the line to earn a short ball to attack on:

Here’s another one against Flavio Cobolli off a floating return that Machac takes early for a Serve +1 winner

We typically see the jumping scissor kick on the backhand side, as a way for players to hit a high quality ball that would otherwise be above their shoulder if they didn’t jump. Machac takes that to its most aggressive iteration: hitting it on the forehand side (the side that most players prefer to generate offense on) and on the rise (before the ball hits its apex). It’s unlikely that we’ll see this shot more than once or twice a match because so many things have to precede it (a short high ball in the general area of his forehand that he can recognize quickly and move forward on), but it is electric when it happens.

Gael Monfils, playing possum

This is a screenshot of Gael Monfils in the second set of his semi-final win against Nishesh Basavareddy in Auckland

Monfils has been like this for quite a few games at this point, barely running for drop shots, occasionally trying to slap a forehand winner out of nowhere to end the point early. He is tired; between points his racquet is used primarily to prop himself up, and when he is returning serve, his body is fully keeled over until Basavareddy begins his service motion. If this match goes to a third set, it seems like Basavareddy would take it by attrition.

Gael Monfils is not a happy camper at this moment.

He then proceeds to earn two break points off of a loose error from Basavareddy, and manages to hang in for one extra ball at 30:40 to get the break. At 5:4, serving for the match, Monfils holds at love (wins all the points in his service game) to move on to the Final.

You would think that his obvious physical discomfort would not bode well for him in the final against Zizou Bergs. You would be wrong, as Monfils plays patient, disciplined, consistent tennis against a misfiring Bergs to take the Auckland title. Let this be known: keeled over Monfils is undefeated, like a Steph Curry 3, a Dirk Nowitzki one-legged midrange, or Arjen Robben cutting to his left foot. He is the “Call an Ambulance” meme of the ATP tour:

Ad Court Biased Court-Level Broadcasts

Talk to any tennis fan about the experience of watching tennis on TV, and eventually you’ll hear them bemoan the lack of court-level camera coverage. By having the broadcast view sit so high up, you see the entire court, but at the expense of missing out on the true speed and reaction times of the players. It’s like seeing a baseball pitch from the typical broadcast angle, which might make you think “that’s fast”, versus seeing a pitch from an umpire cam, which makes you think “how can anybody hit a baseball?”.

As a tennis sicko, I am here to provide an even more specific opinion: we should not only see more court-level coverage, but more court-level coverage that shades towards the ad court (if you are viewing a tennis court from bird’s eye view, think of the ad court as Top Right quadrant and Bottom Left quadrant).

While a tennis match is (mostly) evenly divided between deuce-court serves and ad-court serves, points in modern tennis leans towards ad-court rallies. This is because most players are right-handed, their forehands are more offensive than their backhands, and the biggest advantage that can be generated in a baseline exchange is an inside-out forehand to the opponent’s backhand. If one of the players is left-handed, we often find a similar pattern when the lefty is generating offense, as they try to hit cross court forehands into their opponent’s backhand (think about Nadal’s punishing topspin forehands into Federer’s backhand wing). Showing us more points with a camera sitting slightly behind the ad-court gives the viewer a much better view of what the players are seeing, as well as orients us towards those patterns of play. If Tennis Channel comes out with a premium streaming tier with alternative broadcast views (a la NFL’s All-22), I (and tens of other people) would gladly pay for it.

The AO One Point Slam

Nestled between the exhibition charity events hosted during the Australian Open Fan Week was one of the most hilarious tennis concepts I’ve come across in some time: the One Point Slam.

The tournament is a 32 person singles draw, where the first round consists of 16 matchups between professional players and amateurs. Every match is one point and one point only, with a coin toss at the beginning to determine who serves for the point. Pros get only 1 serve, and Amateurs get the normal 2 serves.

These are the ideal conditions for an Amateur player to win against a pro: 1 point for maximum randomness and chaos, and Pros are robbed of their biggest weapon (their 1st serve).

That being said, the pros are the pros for a reason: after the first round, only 2 amateurs made it to the round of 16. Still, many of the Amateurs made strategic errors: choosing to return when they won the coin toss (a pro’s second serve, even at a charity event, is probably the most difficult shot an amateur tennis player would ever face), trying to beat the pro by exchanging groundstrokes (??), and all the typical amateur tennis follies (going down the line too soon, lazy footwork, going for the knockout punch 6 feet behind the baseline).

And yet, one Amateur player played all his cards right, and made it to the semi-finals; Paul Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald’s first round win (36:37 of the video) against former top-200 player Dane Sweeny was a perfectly placed wide slice serve that Sweeney could not return. He goes for the exact same serve in the second round (47:30) against Matthew Dellavedova (not the former NBA player) and gets another unreturned serve. In the third round (58:05), his opponent Alex Bolt is wise to the tactics, and is expecting the same serve. Fitzgerald responds by cracking a 156km/h (97mph) serve right down the T for an ace.

His cinderella run finally ended in the semi-finals (1:05:51), when his opponent Priscilla Hon chose to return from the ad court. This puts Fitzgerald in a pickle: if he goes down the T again, it’s into Hon’s forehand in the middle of the court, and she could put that anywhere. If he goes wide, he can probably narrow down where she’ll return the ball, but she will absolutely get a racquet on the ball because it isn’t spinning away from her. He chooses to go wide, but also starts his serve from very far to the side of the court to give him more angle.

Unfortunately, he also decides to try for the serve and volley off his second serve, and has too much ground to cover to cut the return off at net. He can only watch the return sail past him for a winner:

Paul Fitzgerald, you’re an absolute legend.